The Story of Soudan, Minnesota and its Mine

Ojibwe living in northeastern Minnesota had long been aware of the presence iron ore deposits in the region. They told blacksmith N.A. Posey about it in 1863, when Posey was living among them to teach them his trade at the request of the US government per treaty agreements. The Ojibwe gave samples of the region’s iron ore to Posey and he shared the samples with area surveyor and civil engineer George Stuntz.

Minnesota was brought into the United States in 1858, a few years prior to the Civil War. Most of Minnesota’s immigrant population was further south, some folks resided in the harbor city of Duluth and there were several settlements along Minnesota’s North Shore. The state government needed to know more about the inland regions to the north and west. George Stuntz, a government land surveyor from Superior, Wisconsin came to investigate and survey the land in Minnesota’s Arrowhead region in 1865, right after the Civil War.

Stuntz arrived at the same time that a gold rush exploded on the southern shore of Lake Vermilion. During the short two-year period that the gold rush had a crescendo and then sputtered out, scores of gold miners and hundreds of new settlers forged The Vermilion Trail, a rugged 100-mile overland route from Duluth to Lake Vermilion. The discovery of gold turned out to be an exciting diversion. The real treasure in the ground was iron ore.

As George Stuntz traversed what would come to be known as the Iron Range, he made a test blast near what would become the Soudan Mine and told Duluth businessman George C. Stone, an aspiring investor, about the promising ore that turned up. They consulted with Edward Breitung, a mining investor from Michigan. Appreciating the high quality of the ore, Breitung made the decision to partner up with George Stone in a new mining venture in Minnesota.

Searching for more investors, in 1875, George Stone presented samples of iron ore from the Vermilion and Mesabi Ranges to Charlemagne Tower Sr., in order to persuade the millionaire Pennsylvania investor to consider joining him and Breitung in developing iron mines on the Minnesota Iron Range. Tower, who had made much of his money in the coal mining industry, a successful lawyer and wealthy land speculator, saw an opportunity and was willing to consider partnering with them. After sending in his own experts, principally geologist Albert Chester, to investigate, he agreed to the become partners with Stone and Breitung and from this partnership, the Minnesota Iron Company later evolved. Tower became the principal partner and chief financier.

In 1879, after demand grew for the low-phosphorous hematite of the Vermilion Range, Tower concentrated his investment in the area now known as Soudan. Tower began acquiring land in Township 62 North, Range 15 West—the area George Stuntz had deemed most promising—by hiring men to claim 160-acre parcels. Rather than establishing homesteads and making improvements, as the law required, the entrymen promptly sold the land back to Tower. This was primarily the area we now know as Soudan.

Shipping the iron ore from the North Shore to refineries on the Great Lakes to the east was a necessary component of a successful mining venture on the inland Vermilion Iron Range. With help from Stone, Tower bought up key pieces of land in northeastern Minnesota and purchased an inactive railroad project, the Duluth and Iron Range Railway. Eventually, this railway would run from Agate Bay on Lake Superior directly to the Soudan Mine. It would provide a way to get the area’s ore from the mine through the swampy forest lands of the Vermilion Range to a shipping port.

Tower continued to purchase additional land around Soudan and to the east towards Lake Superior until he owned over 20,000 acres by the end of 1882. With the help of George Stone who was at various times a member of– lobbyist in — the Minnesota State Legislature, the Minnesota Iron Company acquired the land to build a railroad from Soudan to Agate Bay (now known as Two Harbors) 26 miles north of Duluth on the shores of Lake Superior. It took several years of hard work of sponsoring laws that would be friendly to the effort and cajoling the Minnesota State legislature and individual legislators for George Stone to get the job done.

As it acquired land, the Minnesota Iron Company financed the improvements necessary to settle the area and establish a mine, which was initially called the Stone and Breitung Pits and work began at the Pits in the summer of 1883. Supplies and equipment for the mine such as sawmill machinery and steam boilers were purchased and transported by oxen and on foot, from Duluth to Lake Vermilion and then on to Soudan, by way of The Vermilion Trail, established during the Lake Vermilion Gold Rush in the mid 1860’s, a 100-mile journey that took three days.

Tower insisted that ore shipments would begin as soon as the railroad was finished. At the same time that work began on the mines, work began on the construction of Charlemagne Tower’s Duluth and Iron Range Railway line in the summer of 1883. Fourteen hundred laborers were hired to build a railroad from Lake Vermilion to Agate Bay. Experienced miners were recruited from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and put to work stripping surface material from outcroppings of iron ore near the top of a 300-foot ridge south of Stuntz Bay. Workers created a stockpile of ore in preparation for the first shipment from the mine.

The Duluth and Iron Range Railway arrived at the Soudan Mine on July 30, 1884, and carried the first shipment of almost 3,000 tons back to Agate Bay the next day. A few days later, the ore was loaded onto the steamers Ironton and Hecla and shipped across the Great Lakes to Cleveland. In Cleveland, George H. and Samuel P. Ely sold it for Tower’s firm, the Minnesota Iron Company.

Operation and Control of the Minnesota Iron Company, Oliver Mining Company and US Steel

Soudan miners first dug the mines out using the open-pit technique, since the ore was close to the surface. As the ore was removed to a depth of more than twenty feet, operations shifted underground for safety reasons. By the 1890s, operations were entirely underground. During this period, miners were able to excavate with minimal bracing and little fear of mine collapse, since the ore was hard and ran through the surrounding rock in nearly vertical columns. Miners followed the seams of ore downward, excavating on many levels at once, until the depth of the mine reached nearly 2,500 feet. Initially, compressed air drills and mule power were used to excavate and transport the ore.

Never as big as the Mesabi Range to the southwest, the Vermilion Range and its mines were steady producers of iron ore over many decades. The Soudan Mine peaked in 1892 at 568,471 tons of iron ore shipped.

Later, once it was clear that the Soudan Mine would make money, the Minnesota Iron Company was bought by a group of New York investors and merged with the Oliver Iron Mining Company, which eventually became part of U.S. Steel.

Tower, Stone, and Breitung’s original partnership changed hands several times in the 1890s and became part of the United States Steel Corporation after the turn of the twentieth century. By 1900, the Soudan mine was shipping out an average of one million tons of ore a year, a production rate it maintained until it closed due to dwindling profits in 1962. The mine was electrified in 1924 and an electric hoist, pumps, and crushers were added to the operation.

Eventually, the Soudan mine extended twenty-seven levels below ground, a depth of 2,341 feet. The Oliver Mining Company, a subsidiary of U.S. Steel known locally as “The Oliver,” ran the Soudan mine and most others on the Vermilion and Mesabi Ranges for most of the twentieth century.

Soudan: A “Company Town”

Establishing a mining operation in the rugged, remote area of the Vermilion Range meant importing a skilled and adventuresome labor force. Lured by the promise of good jobs, however, others followed, many of them immigrants from all over Europe and the U.S. In 1883, George Stone hired Elisha Morcom to be captain of the Minnesota Mine. Morcom came from a long lineage of miners from Cornwall, England, and had worked in the iron mines of Michigan’s Menominee Range since the 1850s. Morcom recruited other experienced miners from Michigan; by early 1884, 350 men, women, and children had signed up to move to the Vermilion Range. Additional laborers were employed to form a workforce 500 strong as the first shipment of ore was being readied in 1884.

During those early years, even though he had grown somewhat accustomed to the cold winters of upper Michigan, Morcom and his miners found it to be far more frigid on the Vermilion Range. Morcom jokingly referred to the mine and the area around it as “Sudan”, after the steamy tropical Sudan region of Africa. He meant it in fun but the name stuck. The spelling, however, morphed into Soudan” with an “o”.

Buildings were erected to house the community of miners and their families at several sites near the mine. The municipality of Tower, located less than two miles southwest of the Minnesota Mine, was platted in 1883 with the hope that eventually it would become the seat of a new county. Mining company officials consciously relegated all private commercial businesses to Tower, and that town came to be populated mostly by the wealthier citizens of the western Vermilion Range such as mining company executives, professionals, and business owners.

About twelve unincorporated communities known as “locations” were established by mining companies throughout the Iron Range as residential enclaves for the miners and their families. The Minnesota Iron Company built blocks of houses in Breitung and Stone, the names of the two “locations” near the Minnesota Mine that together came to be known as Soudan, by the late 1880s. The houses, which were small, simply built, and uniform in appearance, were leased to mine workers. Many of the miners eventually were able to purchase their homes, but the lots remained under continuous control of the mining company.

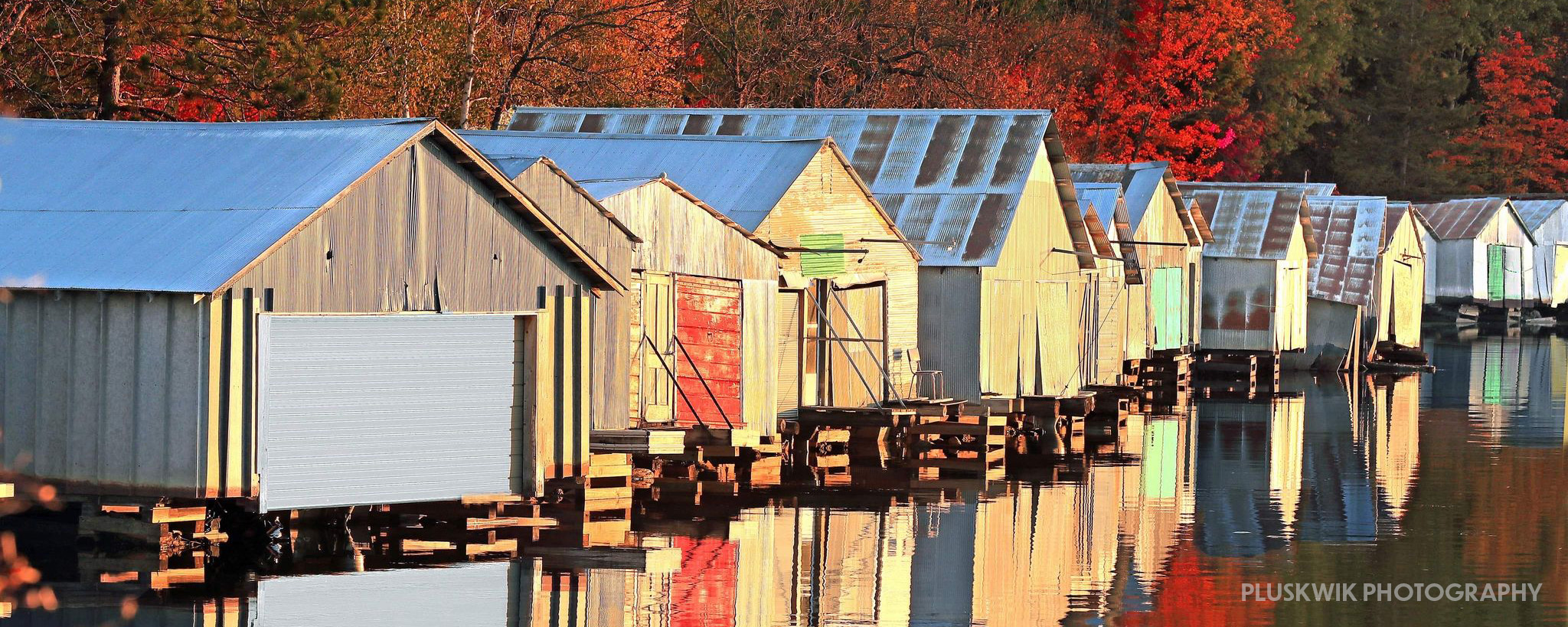

After The Oliver Mining Company (locally referred to as “the Oliver”) took over, services such as water and, later, electricity were provided to the “locations” by the mining company. A pumphouse was built by the company near the shore of Lake Vermilion to pump drinking water over the hill from the lake. Electricity was provided to the “locations” in 1924 when the mine was electrified. By 1945, when, by then the community had become the town Soudan, the mine installed city-wide plumbing. The former pumphouse (#83 in Stuntz Bay) was remodeled as a boathouse sometime after 1950.

Around the turn of the century a hospital had been erected by the Oliver in Soudan and staffed with a live-in doctor to care for ill or injured miners and their family members who designated that $1.00 a month be taken out of their paychecks in exchange for medical care. The same $1.00 a month designation applied to being able to stay in the hospital, if necessary.

Churches, all Protestant, were on many corners of the central part of the community of Soudan. The Catholic church was located in Tower. Thus miners and their families had easy access for involvement in religious venues.

“Successful” Soudan

Mining companies realized that providing adequate housing and services could contribute directly to the maintenance of a stable, efficient, contented, and productive labor force. According to Arnold Alanen, whose essay about townsites and locations on the Vermilion Range is included in Entrepreneurs and Immigrants: Life on the Industrial Frontier of Northeastern Minnesota, the “locations” especially catered to families, given that employees who had wives and dependent children were considered to be the most reliable workers. While relatively well-housed and well-serviced employees could be found throughout the region, the laborers in a company town like Soudan exchanged such provisions for a certain loss of individual rights and expression. Employee behavior that departed from corporate norms either within or outside the work place could be regulated by threat of discharge from one’s company-owned house.

Alanen believes that the community of Soudan, very much a company town, was one of the most successful “locations” established on the Iron Range: Separated by distance, function, and social class from Tower, Soudan was intended by “the Oliver” to house workers who would concentrate upon one activity: the mining of its iron ore. By limiting institutional facilities to those serving health, recreation, and religious needs, Soudan was viewed by mining company executives as an enclave for the housing of contented and efficient workers.

Such laborers, of course, were seen as being able to contribute to increased corporate productivity and profitability. The mining company’s early efforts to promote stability appear to have been successful, as working at the mine became something of a family tradition. Elisha Morcom’s grandson, Ronald, was one of the last Soudan employees when the mine closed in 1962; he worked there over forty-two years, after following his father into the mining business. In 1959, the mine superintendent, Earl Holmes, estimated that most of the 275 men working at the Soudan mine were sons, grandsons, or great-grandsons of Soudan employees.

“The Oliver’s” goal of a content workforce was achieved, whether due to the unique conditions of the underground mine, its relatively high and consistent profitability, the close kinship of its workforce, or the company’s benevolent tactics. Labor unions were not introduced at the Soudan mine until 1937, and there were no significant strikes or other signs of labor unrest at the mine during its seventy-eight-year history.

Recreation and Leisure

Despite the looming presence of the mine, daily life in Soudan was not all work and no play. Hunting and fishing appear to have been the primary leisure-time pursuits of the miners and their families. In 1959, mine superintendent Holmes acknowledged that the miners “like this country on the shore of Lake Vermilion with the boating, fishing, and hunting.”

Mining company publications such as U.S. Steel News, an internal magazine, promoted the recreation of the North Woods. For example, the heading over a photographic spread in the June 1937 issue of this publication stated: “Beyond the Mines Lies Vacationland.” The caption reads, “Lakes, forests, fish and game are close at hand in the iron range country.” Oliver Mining Company employee handbooks and recruitment materials also emphasized the outdoor recreation opportunities in the area, with photographs of men and women canoeing, waterskiing, fishing, and hunting. The group of 151 boathouses–almost two-thirds of a mile long–along the shoreline of Stuntz Bay stands as testament to the miners’ leisure activities on Lake Vermilion. The boathouses were owned by the miners, the land beneath them by the mine. The boathouses were passed on in families from generation to generation.

Soudan, In Retrospect

The Soudan mine enjoyed decades of prosperity thanks to the unique composition and purity of the ore, which had a particular use in the steel-making process, and its seemingly inexhaustible supply. In the 1890’s the mining operation moved underground when the open pits grew deep and increasingly dangerous. In the underground mining operation, the dense greenstone surrounding the ore veins allowed for the underground mine to be extended with minimal timber shoring and reinforcement. Compressed air drills and mule power were initially used to excavate and transport the ore from under the ground but in 1924, with the electrification of the mine, an electric hoist, pumps, and crushers were added to the operation. Eventually, the Soudan mine extended twenty-seven levels below ground, a depth of 2,341 feet. It reliably produced tens of thousands of tons of ore every year from its opening in 1884 until its closing on December 15, 1962, with more than fifteen million tons shipped over the life of the mine

The Mine continues, but in a different capacity. It is now the centerpiece of Soudan and focal point of the Lake Vermilion-Soudan Underground Mine State Park. The park was created in 1963 when the mine property was transferred from U.S. Steel to the State of Minnesota and opened for tours in 1965. For many decades, the Mine Interpreters have been the children and grandchildren of the miners of past generations, thus carrying on the tradition of members of the town continuing to honor, appreciate and love the town from which their ancestors came and in which their families survived and thrived.

Sources:

Erin Hanafin Berg and Charlene Roise, “Stuntz Bay Boathouse Historic District,” January 2007, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, State Historic Preservation Office.