Tower Train Depot Museum

Although the building is often referenced as the Tower Depot or the Duluth, Missabe and Iron Range Railroad Depot, its original, or historic, name is the Duluth and Iron Range Railroad Company Passenger Station. This name is derived from the building’s architectural drawings, which were produced in 1916. It should be noted that the building is actually the second train depot in Tower.

Duluth and Iron Range Railroad Company (D&IR) Freight Depot

Tower’s first train depot, labeled on early maps as the “Tower Passenger Depot” was later referred to, from 1921-on, as the “Duluth and Iron Range Freight Depot”. This Freight Depot had been constructed sometime between 1884 and 1886 on the western edge of the town along what is now the intersection of Highway 169 and Cedar Street, with spurs running to the Soudan Mine for iron, and to HooDoo Point for timber. It was also used for storage, and housed the telephone exchange.

The building itself was extremely modest, a long, narrow, one-story wood frame building with a projecting bay on one side and a covered platform. It was unadorned and utilitarian. The early trains and depot were owned and operated by the Duluth and Iron Range Railroad Company, which was owned by Charlemagne Tower.

The Duluth and Iron Range Railroad Company Passenger Station

In the late 1800’s, the area around Tower began to emerge as a tourist destination. Roads were not plentiful in the area; rail travel was the best and most reliable mode of transportation at that time. As years went by, tourism was promoted. Word had spread about Lake Vermilion and the other beautiful lakes in the area, where the fish and game were plentiful and the air was healthy. Tourism to the area was given an extra push by extensive promotion by the D&IR, beginning in 1908 under General Passenger Agent H. Johnson. The railroad, perhaps sensing an expansion opportunity, was an early and ardent supporter of Lake Vermilion tourism. The D&IR, leading the growth of that industry decades ahead of other Minnesota recreational centers, would play a significant role in Minnesota resort tourism.

Each year, the number of visitors to the area increased and when they arrived in Tower, they disembarked onto the platform at the Freight Depot on Cedar Street. Although this depot had been (incorrectly) described as a “passenger depot,” the design alone indicated that passengers were little but an afterthought to timber and iron transportation. The long, barnlike space included little in the way of passenger comforts; its style and functionality displayed its freight-oriented roots, and its location was not ideal for expansion, parkland, or water access.

One thing became clear — to meet the increased customer service needs of a tourism-based economy, Tower and the Lake Vermilion gateway would need a more welcoming depot. The D&IR decided that these northland visitors should disembark from their railroad journey into a well-appointed welcoming depot. A brand-new building was needed to accommodate the eager visitors who wanted to take advantage of the amenities the area had to offer. Plans were made to build a second train depot in Tower, exclusively for tourists.

It was thus with great excitement that the Tower Weekly News announced on February 4,1916; “New Depot Assured.” In July of that year, the News asserted:

“With the present growing passenger service of the railroad and with a future outlook that is good, a new depot is needed. Lake Vermilion has just begun to pull. Each year from now on the crowds will increase. The new depot will properly greet the new arrivals and care for their needs in a first class manner.”

The long-promised new depot would be built in parkland just west of the Tower downtown and approximately 250 feet southeast of the old freight depot. The new facility would not only provide expanded services and amenities for the rail line passengers, but also supply closer access to water transport onto Lake Vermilion. The new structure would be built adjacent to the “Tower Harbor,” a widening in the East Two Rivers waterway, and near the town’s historic 1901 McKinley monument. From here, it was envisioned that passengers could disembark from the train, stroll to the harbor, and be ferried by one of the boat services to Lake Vermilion resorts. This siting, however, basically turned its back to downtown Tower, and residents and businesses on the eastern end of Tower petitioned the D&IR for a more inclusive location but, probably due to enabling visitors convenient access from the Depot to the harbor, the railroad denied their request.

The city harbor, established in 1865 and located on a naturally wide point at the bend of the East Two Rivers, provided relatively easy water-based transportation to the lake’s long shoreline and 365 islands, without the delay and expense of roads and supporting infrastructure.

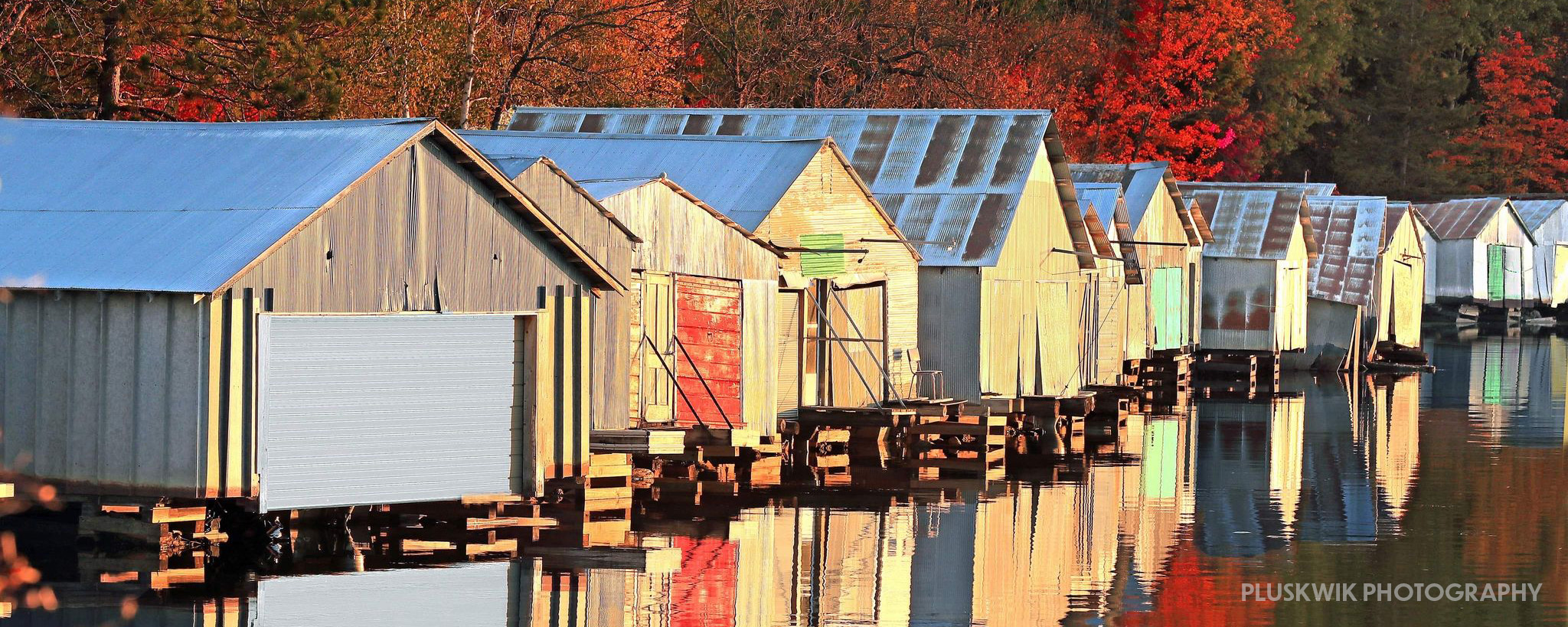

Maps show that the harbor was well-developed by the mid-1910s, including 40+ wet boathouses, 2 ice houses, 2 soft drink storage houses, and 6 multi-vehicle automobile garages. Major boating liveries included the Vermilion Boat and Outing Company, Aronson’s, Bystrom Boat Works, and Gruber Brothers. These companies operated everything from steamboats to speedboats. In addition to passenger service, they carried freight and the mail.

The Duluth and Iron Range Railroad Company Passenger Station – Tower, Minnesota, was built in 1916. The railroad line ran to the southwest side of the depot, with a wide, covered passenger platform. The first D&IR train arrived at the new depot at 7:35am on November 25, 1916.

Construction of the Building

The 1916 depot was built specifically as a passenger depot. Designed by architect William H. Beyrer of Duluth, it was built by contractor George Spurbeck of Two Harbors for the cost of $10,000. The Tower Weekly News reported on 21 July 1916 that work commenced to build it.

As was typical for this style of depot, a ticketing office was centrally located in the building; in Tower, this room also served as the post office, with a central double desk and mail sorting bins on one wall. Tickets were purchased through a ticket window in the main corridor “Ticket Area” which connected the women’s and family’s waiting room to the southeast and the single men’s waiting room to the northwest.

The baggage room was located off of the men’s waiting room at the northwest end of the depot and had some freight capacity, though presumably larger freight was handled at the terminus of the spurs.

The building had a partial second floor located above the ticket office, providing slightly more space and comfort for the “telephone girls” than the previous depot. (The telephone office, which had been in the Freight Depot was moved to the Passenger Station.) Interior floors, woodwork, and design were all solid and presentable, if not elaborate. The waiting platform was concrete, rather than the wood construction of the old depot, and wide eaves provided cover from the elements. Exterior walls were stucco and wood. Though the general style was simple and vernacular, the new structure was stylistically a strong contrast to the box-like, wood-frame Freight Depot.

Tower bolstered this service with a thriving city harbor, adjoining the depot, where passengers could disembark and then utilize boat services to get to Lake Vermilion’s busy lakeside resorts, many of which were only accessible by water. From the Tower Depot, most passengers would make their way to the city’s nearby harbor and board a steamboat to be taken to their destination on Lake Vermilion. Tower (and later Ely) were important early outposts due to their convenient rail access, with service of up to three trains a day.

The D&IR thus facilitated the development of the resort and tourism industry on Lake Vermilion and the surrounding area throughout the early part of the twentieth century, several decades before tourism became an important industry in St. Louis County and throughout the State of Minnesota by allowing early access to, and promotion of, the northern Minnesota lake region. While much of the tourism for the area and statewide was highway-dependent, and thus did not develop until the mid-twentieth century.

The booming tourism of the first part of the twentieth century began to decline by the late 1930s- early 1940s. By then, improved road and highway service, greater automobile ownership and usage, and increased leisure time meant that much of the state had opened up to tourism, and Lake Vermilion no longer held a competitive advantage. Auto-related industries, such as the Minnesota Scenic Highway Association, began extensive promotional campaigns that overshadowed the Duluth Missabe and Iron Range Railway (DM&IR) efforts. (A combination of multiple rail lines created the DM&IR in the 1930s.)

These factors contributed to a decline in railway ridership. As the interstate highway system developed and international travel became more popular following WWII, Minnesota lakeside tourism began to decline. The statewide context “Minnesota Tourism and Recreation in the Lakes Region” defines the main period of influence as ending in 1945.

In Tower, Minnesota State Highway 169 was extended and re-routed in 1948, which caused a re-alignment and reduction of the harbor beginning in the late 1930s. With declining ridership, the DM&IR ceased passenger service in 1951, and discontinued freight service for iron ore in 1962 after the Soudan mine closed.

The Tower Train Station remained unused until 1966 when DM&IR donated the building to the City of Tower.

The depot was added on the National Register of Historic Places June 14, 2013, listed as the “Duluth and Iron Range Railroad Company Passenger Station”.

The TSHS entered into a lease agreement with the City of Tower in 2007 to operate as a historical museum. Displayed on tracks adjacent to the structure are a collection of restored cars associated with uses at the depot, including: a steam engine with a coal tender, passenger car, worker’s car, and caboose.

Lasting Impact

Without the promotion of the D&IR, and the resulting construction of the Tower Depot, the area would likely not have been able to pioneer Minnesota’s unique lake resort identity. The depot was important not only as Tower’s passenger depot, but especially in relationship to the river harbor access that allowed passengers easy access to boat services taking them directly to resorts. The resorts, many of which grew out of homesteaded properties and lake landings, thus developed in a symbiotic relationship to the depot and the harbor.

This early tourism, much before lake region tourism in the rest of the state, allowed Tower continued prosperity as timber and iron resources began to dwindle. Lake Vermilion became an early lake tourism destination, and its beauty and popularity set the stage for the Voyageurs National Forest and Boundary Waters Canoe Area and for the outdoor tourism the Arrowhead region is known for today. Unassuming as it may initially seem, the Tower Depot is a pivotal resource in this important Minnesota industry.